French 75: The Evolution of a Celebratory Cocktail

As we sit back, resting from the months of holiday preparations and celebrations, we are faced with a choice: Shall we toast to the end of 2017 and the beginning of a New Year with the traditional sparkling wine or with a fine cocktail? At KOVAL, we always have a third, roguish option: Both!

There’s something delightful about that time-honored cocktail, the French 75, bubbling over with both Champagne and Dry Gin. That’s why every time the New Year comes around, we reach for our favorite variations on the drink. But where did this “Tom Collins in a Tuxedo” come from? And why do we drink Champagne—with or without gin—on New Year’s anyway?

This tradition happens to be much younger than our nostalgia suggests. Like cocktails themselves, the merriment of New Years’ celebrations as we know them today only began to take shape in the mid-1800s. At the time, what we now call traditions, in fact, were highly contested creations. Class lines drew the boundaries of the rivalry, the common folk engaging in parades bordering on joyous riots, with blazing guns and endless noise-making. Naturally, these cultural lines also distinguished who drank what to get their celebration on. While the riotous folk drank beer and whiskey to fuel their parading (and thensome), the new middle class preferred courtly parties and gift-giving, most often recreating what they imagined those of the most elite fashion were doing. That is, what Parisians were doing. And in the American imagination, Paris meant Champagne.

For a long time, effervescence in wine was seen as a flaw by wineries, not a delight. Opening a cask of wine and meeting a bunch of fuzzy fluid showed that a cold winter had stopped fermentation prematurely, and the yeasts had started fermenting again when spring arrived. Thankfully, tastes changed and science advanced. A man considered the “father of modern wine,” Louis Pasteur, figured out how fermentation itself occurred. Up to this point, civilizations knew how to produce alcoholic beverages but not why or how they came to be. At the time, Pasteur’s contribution informed wine producers in Champagne when they figured out that they could control the second fermentation that created their wine’s characteristic fizz. This development made the production of Champagne into a mass-marketable creation worthy of thousands (and today, perhaps billions) of merry toasts. Without Pasteur’s scientific work, beer and wine and spirits could not be what we know them as today.

By the nineteenth century, the celebratory connotation of Champagne had cemented itself into bourgeois society in France, synonymous with the new mercantile class, taking the world from newly disempowered royalty. Alongside France’s rapidly changing sociopolitical environment, Champagne helped define boundaries and personal place during the chaotic shifts of who was in charge of the country. In other words, the charismatic bubbly wine became the aspirational drink of choice, removed from everyday trials and tribulations. What better beverage to ring in a new year and set yourself apart when the middle-class was young and still forming its identity? But that position was about to change drastically.

In the United States, we place a lot of responsibility for changes in drinking culture here (and even abroad) on Prohibition. While the “dry” period in American history certainly had a huge impact, it was only one of many influences. After all, pre-Prohibition drinking in the United States greatly differs from even the worst drunkenness today. Up until the mid-1800s, children and adults were drinking literally all day. Furthermore, what temperance movements existed at that time largely only took issue with hard liquor. Beer and wine weren’t even the subject of most calls for temperance. Bubbly bottles of wine might have survived Prohibition given its tame association with bourgeois parties.

However, World War I irrevocably changed the landscape of wine production in northern France. Reims was bombarded by German artillery for 1,051 consecutive days. Vineyards in the Champagne region were devastated, and soldiers of all allegiances helped themselves to whatever bottles were nearby. Men died in the trenches while women and children left to tend what few vines survived chemical warfare. Before Prohibition hit American markets, the war and subsequent economic decline of Western Europe rendered the king of sparkling wine impotent. So, we turned to hard liquor, with as much ravenous appetite during Prohibition as beforehand if not more.

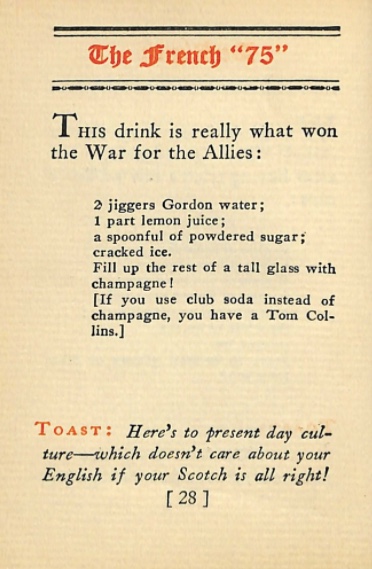

From Here’s How, the little cocktail book published during Prohibition under the pseudonym “Judge Jr.” - 1927

From Here’s How, the little cocktail book published during Prohibition under the pseudonym “Judge Jr.” - 1927

Cocktails took on the charm and elegance previously associated by Champagne. Admittedly, not many Prohibition Era cocktails were actually created in the US, but rather by Americans elsewhere. The one exception to a drought of cocktail creativity during the Great Drought was a little cocktail now known as the French 75.

A lot of similar—yet conflicting—stories surround the origin of this cocktail. Ingredients of gin, lemon juice, sugar, and Champagne had been combined by bartenders before, even if not recorded in writing. Literacy mattered less than actually making a drink for a bartender. (A story of Charles Dickens ordering gin in Champagne cups in Boston presently circulates the Internet, although an original recording of that story has yet to surface.) Some suggest that the French 75 originated alongside its christening with the name of a French field artillery gun used in World War I for the quick-fire delivery of shrapnel and gas shells. Allied soldiers making Toms Collinses with Champagne in the place of scarce soda water, drinking beside one of the most advanced war machines available certainly makes for a good story.

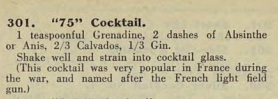

From Harry McElhone’s ABC of Mixing Cocktails - originally published in 1925

From Harry McElhone’s ABC of Mixing Cocktails - originally published in 1925

Each of the earliest printed versions of the French 75 cocktail deliberately draw attention to a connection between the drink and the war. The first known printing of the French 75 came out in a little 1927 book, Here’s How!, by Norman Anthony (under the pseudonym “Judge Jr.,” as this was during Prohibition). Here it’s introduced as the “drink is really what won the War for the Allies.” By 1930, the recipe was picked up and published in The Savoy Cocktail Book by Harry Craddock of the Savoy Hotel in London. With red ink, he added one of his sparring notes underneath the French 75, that the cocktail itself “[h]its with remarkable precision.” However, in an earlier publication, Harry’s ABC of Mixing Cocktails, a cocktail book by Harry of the Parisian Harry’s Bar, has a “‘75’ Cocktail” that also references the drink’s connection to the WWI canon: “This cocktail was very popular in France during the war, and named after the French light field gun.” Yet this cocktail calls for grenadine, absinthe, calvados, and gin, hardly like the French 75 we know today at all.

Given the state of Champagne’s vineyards during the war—not to mention the post-war exodus of American creatives just looking for a (legal) drink—the case for soldiers in trenches waiting long enough to mix the nearest bottle of bubbly with anything else before imbibing it seems slim. Nonetheless, that image must have resonated with bartenders and drinkers of the 1920s and ‘30s, a delicious cocktail emerging from the ashes of war memories. With a name nostalgic of a modern killing machine, the French 75 symbolized anticipated glory, chic bourgeois aspirations, and dashed hopes in the face of trench warfare. By making use of the then out of fashion Champagne, toasting to war-torn northern France, whoever created (or at least named) the French 75 seems to have both honored the past and its traditions while also going their own way, creating something new and old all at once.

The Midnight Soirée, a hibiscus-infused variation made with KOVAL White Rye and Rosehip Liqueur (recipe below). Photo: Belen Aquino, courtesy of Valcohol

The Midnight Soirée, a hibiscus-infused variation made with KOVAL White Rye and Rosehip Liqueur (recipe below). Photo: Belen Aquino, courtesy of Valcohol

Here at KOVAL, we strive to do the same thing. Our modern spirits owe so much to those who came before us; at the same time, we seek to move forward on our own unique path of creating spirits. That means using organic ingredients that we distill grain-to-bottle in our favorite city, Chicago. As the first distillery to open in Chicago since the mid-1800s, we take great pride in ushering local Midwestern grains throughout the entire distillation process. It also means using only the heart cut of our distillates in KOVAL whiskeys, gins, liqueurs and more.

Our Dry Gin’s floral/citrus flavor profile lends itself readily to a traditional French 75, as well as more recent reinterpretations, and our whiskeys lend depth and warmth to other modern renditions. Try one of these French 75 variations as you ring in 2018. Happy New Year!

The French 75

1 oz KOVAL Dry Gin

1/2 oz simple syrup

1/2 oz lemon juice

Champagne

Combine KOVAL Dry Gin, simple syrup, and lemon juice in a cocktail shaker with ice. Shake vigorously for 15-30 seconds. Double strain into a Collins glass or flute, top with Champagne and garnish with a lemon twist.

The Auld Lang Syne

1 oz KOVAL White Rye Whiskey

1/2 oz KOVAL Ginger Liqueur

1/2 oz lemon juice

Top with sparkling wine

Combine KOVAL White Rye Whiskey with KOVAL Ginger Liqueur and lemon juice in a cocktail shaker. Add ice. Shake vigorously for 15-30 seconds. Double strain into a Collins glass or flute, top with sparkling wine and garnish with lemon peel and candied ginger.

The Midnight Soirée

Recipe courtesy of Valcohol

1.5 oz hibiscuis-insused KOVAL White Rye*

1 oz KOVAL Rosehip Liqueur

Juice of 1/4 lemon

Cava, to top

Add first three ingredients to a shaker with ice and shake until chilled. Strain into your favorite festive glass and top with Cava to taste.

*To make hibiscus-infused white rye, add 4:1 ratio of white rye to dried hibiscus flowers to a mason jar and allow to sit for 5 hours, shaking occasionally. Strain, label and store unused portion for up to several months.